When will we know won won the trade?

As trade season approaches, it's good to keep in mind that it sometimes years before we can tell — and it can debatable even then. Plus, was this guy the spittin' image of a memorable pitcher?

Dreammediapeel | Dreamstime.com

TOP OF THE FIRST

Just spitballin’: A truck driver’s tale

I doubt I will ever again meet anyone in a bar as interesting as the only son of the last pitcher who could legally throw a spitball in MLB.

This is in part because I no longer frequent bars. But mostly I blame the Internet.

You used to meet the most interesting people. You’d meet people who invented things, were closely related to famous people, appeared on TV shows or in commercials years ago, played drums for a band that had one hit in the 1960s, pitched for several years in minor-league baseball, or were long-forgotten fringe players on football teams that won the Rose Bowl or went to the Super Bowl.

And you wouldn’t just meet them in bars. You could meet them at the counters of restaurants like Denny’s, or while waiting in line at a store or in a fast-food joint. I seemed to be a magnet for these folks, although I am in no way outgoing.

One that stands out is the only son of Burleigh Grimes. When baseball outlawed the spitter and other pitches that involved doctoring the ball, a few pitchers who relied heavily on such pitches were allowed to keep throwing them. Grimes was the last who played in organized baseball, finishing his career in 1934 with the Pirates.

One night I was with some friends at the Ramada Inn in downtown Phoenix and we met a short, stout man who looked to be in his 50s and was missing his two front teeth. He said he was a truck driver from Miami staying at the hotel. The Ramada was situated across Polk Street from the Arizona Republic and Phoenix Gazette building, and the hotel’s bar served as the unofficial watering hole for the newsrooms.

The truck driver found out we worked in the Sports Department and dropped his nugget — he was Grimes’ son.

He said he did not know his father well. The spitballer had divorced the truck driver’s mother when the lad was young.

Burleigh hadn’t done well in his post-playing days and died relatively young and broke — a sad tale that’s all too typical.

The truck driver was entertaining. We paid for his drinks. I saw him a few other times in there. One time, he and one of my bosses discussed the journalistic merits of the Kansas City Star and Kansas City Times. (The truck driver had lived in Kansas City for a while.)

The good news is that Burleigh Grimes did not die young or penniless. In fact, as the truck driver was spinning his tale in the early 1980s, Grimes was still alive.

Grimes did find work after his playing days. He managed the Dodgers for two seasons and managed in the minors for decades. He was a scout for the Orioles until 1971.

Grimes was married five times, but as far as anyone knows, he didn’t have any children.

Today if you met someone like that truck driver and he told you a tale like that, you’d just take out your phone, do a quick Google search, and the fabulist would be busted!

And an evening’s entertainment would be gone.

HEART OF THE ORDER

What’s the deal?

Brock-for-Broglio shows it’s hard to say immediately who got the better end of the trade

We are coming up on the 60th anniversary of one of the best-remembered, most lopsided trades in MLB history

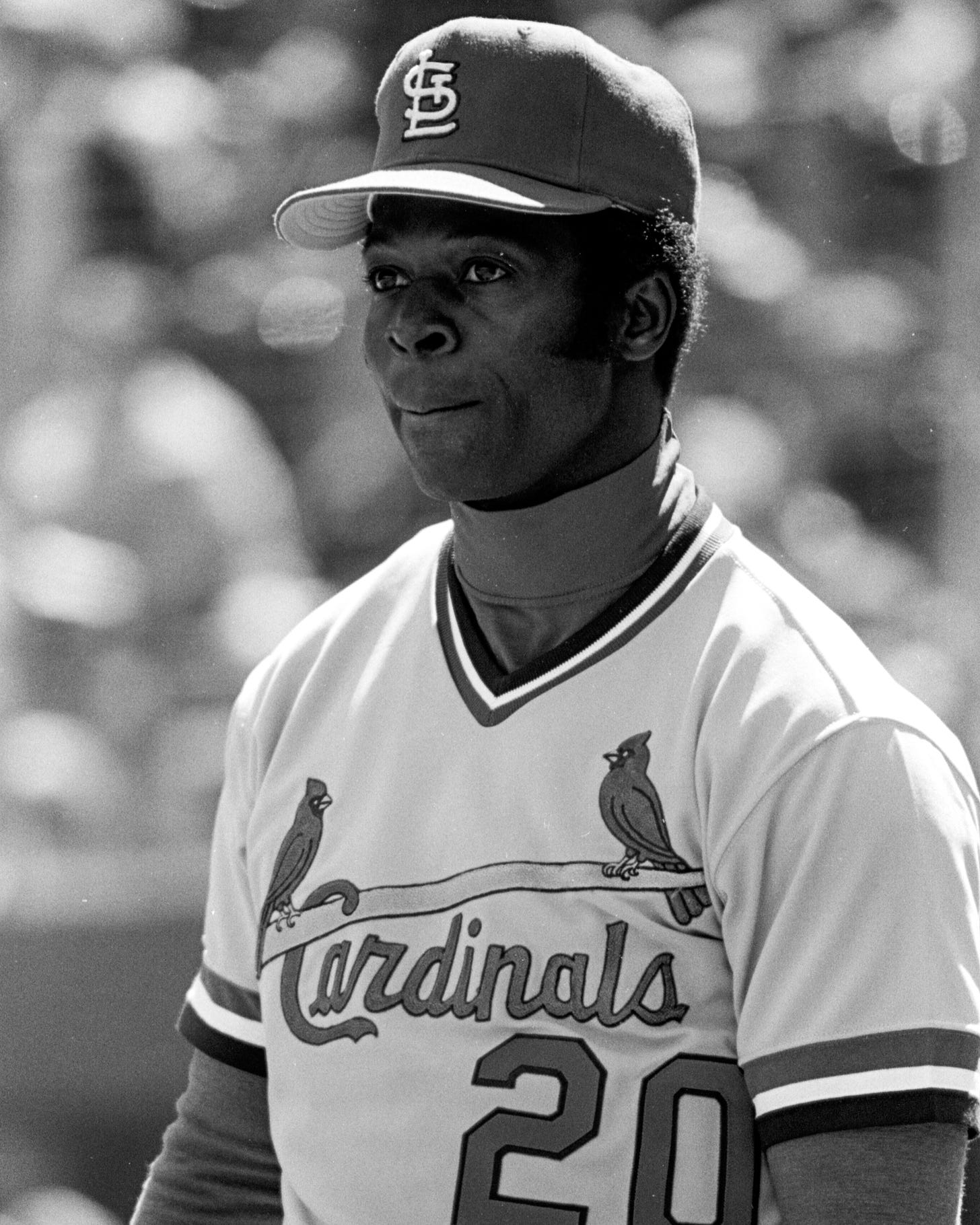

On June 15, 1964 the Cubs traded outfielder Lou Brock to the Cardinals for pitcher Ernie Broglio (There were four other players involved, but those two were the headliners.)

Brock went on to a Hall of Fame career with the Cardinals, hitting .348 the rest of the season, and it’s doubtful they would have won the National League pennant and World Series without him.

Broglio compiled a 5.40 ERA in two-plus seasons with the Cubs. This was in an era when the MLB average ERA was around 3.50. He spent 1967 in the minors with the Reds’ AAA team in Buffalo and retired.

Just as you can’t judge a book by its cover, you can’t judge a trade by its coverage.

“Thank you, thank you, oh, you lovely St. Louis Cardinals.” Bob Smith wrote in the Chicago Daily News the next day. “Nice doing business with you. Please call again any time.”

There was a lot to like from the Cubs’ perspective. Broglio led the majors in pitching victories — then the coin of the realm in baseball — with 21 in 1961 and went 18-7 in 1963. Brock was hitting .251 in his third full season with the Cubs.

And few remember that the Cardinals were so thrilled with the deal that they sacked their GM, Bing Devine. That’s right, on Aug. 17, two months and two days after he pulled off one of greatest deals in MLB history, Bing Devine was fired. (More on Bing and this trade below.)

And that’s the thing with trades. Everybody knows or thinks they know the impact of a trade. And we don’t know. In some cases, it can be in dispute decades later. And opinions can change.

D-backs trade that led to the World Series

In December 2022, the Diamondbacks traded Daulton Varsho, perhaps their best position player, to the Blue Jays for Lourdes Gurriel Jr. and Gabriel Moreno.

Varsho, who was heading into his age 26 season, has unusual versatility. He can play catcher and center field. He is a left-handed batter, a major reason why Toronto wanted him. In 2022 he ranked fourth in the National League in Power-Speed number, a measurement developed by Bill James to measure . . . well, power and speed. Varsho’s big deficiency is a low batting average. His career high is .241.

Gurriel was heading into his age 29 season and coming off a year in which his home run production dropped from 21 to 5. He is a left fielder with decent range and a suspect arm. So he needs to hit some homers.

Moreno, heading into his age 23 season, he was a top-catching prospect because of his defense, although he hit .311 in the minors and .319 in his 25 games with the Blue Jays. He was initially expected to back up Carson Kelly.

Avg. OPS+ HR WAR

Varsho 2022 .235 108 27 4.8

Gurriel 2022 .291 114 5 2.2

Moreno 2022 .319 112 1 0.7

The Blue Jays saved a few dollars on the deal as they tried to stay under the luxury tax threshold.

To me, it looked like a wash that depended a lot on how Moreno turned out. Varsho was probably a better player than Gurriel.

Avg. OPS+ HR WAR

Varsho 2023 .220 85 20 3.9

Gurriel 2023 .261 109 24 3.0

Moreno 2023 .284 105 7 4.3

Gurriel and Moreno were instrumental in the D-backs making the playoffs and getting to the World Series.

Kelly was injured in spring training, which gave Morneo the lead-catching job. I find it hard to believe that wouldn’t have happened anyway. Moreno led the majors in defensive WAR (3.1) and won a Gold Glove.

His bat got better as the season went on. He hit .312 with a .894 OPS after the All-Star break.

Kelly came back, appeared in 32 games, and was released. He is with the Tigers now.

Gurriel was on fire early in the season, hitting .295 through the end of May with nine homers. He made the All-Star team on the strength of his early performance. He cooled down in June and July batting .174 during that stretch. He regained his early season form down the stretch, hitting.291 with nine homers after July 31.

He also had the best defensive season of his career with 14 DRS.

The D-backs re-signed Gurriel for three years for $42 million and a club option for a fourth.

Although he still homered a lot, Varsho’s production at the plate suffered, but he managed to complete an impressive WAR.

After the 2023 season, the deal looked like a win for the D-backs. They received two key performers instead of one, and Moreno looked like the next Ian Rodriguez.

Now let’s look through June 13 of this season.

Avg. OPS+ HR WAR

Varsho 2024 .217 114 10 2.7

Gurriel 2024 .247 96 9 0.5

Moreno 2024 .240 95 2 0.8

When it comes to batting average, none of these guys will be mistaken for Luis Arraez.

Varsho is one of the few bright spots in the Toronto offense, which, to the surprise of many, is now home-run challenged. The Blue Jays are tied for 26th in homers with 56. Varsho’s10 homers are two more than Davis Schnieder, the Jays’ second-leading home run hitter.

Varsho leads the team in WAR. And he is making $5.6 million, less than half what the D-backs are paying Gurriel. So if the season plays out like this, I may be re-evaluating again.

A few words about the Smoltz-Alexander trade

One deal that makes most lists for the most lopsided trades is the 1987 deal in which the Tigers sent future Hall of Famer pitcher John Smoltz to the Braves for pitcher Doyle Alexander. But not on mine.

The deal was praised at the time because Alexander pitched brilliantly down the stretch, going 9-0 with a 1.56 ERA, and helped the Tigers win the American League East title.

As I have written, the window was closing on the Tigers’ championship aspirations in that era. If they had kept Smoltz, they still would have been unable to make the postseason in the 1990s.

But clearly, the Braves got more in value in the long run.

Oh, brother: Pedro Martinez for Delino Deshields

The Dodgers traded away Pedro Martinez, one of the best pitchers of his era, because of the perceived shortcomings of his brother. Older brother Ramon Martinez, who went 20-6 with a 2.92 ERA with an MLB-leading 12 complete games in 1990, was brilliant but seen as somewhat fragile.

Ramon was 6-foot-5 and weighed 165 pounds.

Pedro was 5-11, 170. He threw hard — for the era — reportedly 90 mph. In one partial season and one full season with the Dodgers, Pedro went 10-6 with a 2.58 ERA. He was used primarily as a reliever, starting only three of the 67 games he pitched for the Dodgers.

Delino DeShields looked to be an up-and-comer at second base. Through four seasons with the Montreal Expos, he hit .277 with an on-base percentage of of .367 and 181 steals. He was entering his age 25 season and looked like a budding star. He was also getting a little expensive for the Expos. He made $1.5 million in 1993.

The Dodger needed help at second base. So they made the deal.

DeShields had a solid career but never blossomed into a star. In three seasons with the Dodgers, he never hit higher than .256.

Martinez went on to win three Cy Youngs and was an eight-time All-Star. In 1997, he led the majors in ERA (1.90.) This was at the height of the steroid era.

You can’t always get what you want

The Angels traded Jim Fregosi, who had been the face of the franchise for most of the team’s existence, to the Mets for Nolan Ryan and three prospects. It seemed pretty even at the time.

This is memorable because the Angeles ended up replacing one face of the franchise with another — and because of who wasn’t involved.

Fregosi was a six-time All-Star at shortstop who was heading into his age 30 season. He had a down year in 1971 because of injuries through 1970 he was a .277 hitting with 118 career OPS-plus.

The Mets thought they could contend in 1972 with a solid third baseman. The Angels wanted an MLB-ready pitcher. Specifically, they wanted Gary Gentry, the Mets’ No. 3 starter. The Padres also wanted Gentry that winter.

The Mets offered Ryan instead, and the Angels accepted.

Ryan was “said to have the potential of a Sandy Koufax,” Ross Newhan wrote for the Los Angeles Times. Indeed he did. Koufax had pitched a record four no-hitters with the Dodgers and Ryan pitched four no-hitters for the Angels. He was a five-time All-Star before the team let him go as a free agent.

Gentry went 7-10 with a 4.01 ERA for the Mets in 1971 and was traded to Atlanta, where he developed elbow problems, He retired in 1975.

Fregosi hit .232 with an OPS-plus of 89 for the Mets in 1972 and they traded him midway through the 1973 season. He returned to the Angels as manager in 1979 and, with Ryan leading the rotation, led the team to its first division title.

Ryan pitched in the majors until 1993. The Angels retired his number while he was still pitching for the rival Texas Rangers. Well into the 2000s, you would see many more fans wearing Nolan Ryan jerseys than any other player at Angels Stadium.

The blockbuster deal: Colavito for Kuenn

On April 17, 1960, Easter Sunday, Cleveland sent 1959 AL home run champion Rocky Colavito to the Tigers for 1959 AL batting champion Harvey Kuenn.

They don’t make trades like this anymore, where teams exchange two position players at or near their prime who were coming off All-Star seasons.

And no one would trade a power hitter for a batting champion who hit more than 10 homers only once in his career. Batting average just isn’t valued the same way it was back in the day.

But in 1960 batting average was the coin of the realm.

Rocky Colavito was 26 and hit 129 homers in four full seasons. he was handsome, outgoing, and immensely popular with Cleveland fans.

The team now known as the Guardians was playing an exhibition game in Memphis two days before the season opened. (This was the last year of the AL using a 154-game season, and scheduled doubleheaders were still a thing, so the season began in mid-April.) Colavito was standing on first base when he got the news.

He was baffled by the trade. Now 1959 had not been quite as good for Colavito as 1958. In ’58 he hit 41 homers but his batting average was .303 and his sluging pct. was an MLB high .620. In 1959, his average dipped to .257. He also struck out too much for General Manager Frank “Trader” Lane’s liking. From 1957 through 1959, Colavito averaged 85 strikeouts. By today’s standards that wouldn’t raise an eyebrow, but it was a different game.

Colavito wanted more money. He asked for a raise — $7,000 — and Detroit Timesreluctantly gave it to him, paying him a princely sum of $35,000. It probably wasn’t the money as much as Colavito asking for it that Lane didn’t like. Kuenn was making $40,000.

At the time of the deal, Kuenn was a seven-time All-Star and a former Rookie of the Year. He was more versatile on defense than Colavito, Kuenn had come up as a shortstop, and he could play the third and center field, plus the corner outfield spots and first base. Colavito was strictly a corner outfield and first baseman.

Keunn was coming off a season in which he hit .353 and slugged .501. He hit nine homers and struck out only 37 times.

As providence would have it, Cleveland was opening the season in Detroit.

Colavito had to fly with his now-former teammates to the opener.

Though he had moved north, things went south for Colavito. The Tigers won their first five games of the 1960 season, then lost the next 10. They were never better than .500 the rest of the season and finished sixth with a 71-83 record.

Colavito got off to a slow start, batting .184 with RBI through the team’s first 31 games and garnered much of the blame. Joe Falls of the Detriot Times was unimpressed with the combination of Colavito’s cockiness and poor production. Falls invented a stat for Colavito called the NRBI — Not RBI — for runs that Colavito failed to drive in.

He finished the season with a .249 batting average, 35 homers and 87 RBI.

Cleveland, which had finished second to the White Sox in 1959, slumped below .500 and fell to fourth place. Kuenn hit .308 with nine homers and was dealt to the Giants after the season.

Colavito bounced back in 1961, hitting. 290 with 45 home runs and 140 RBI. 1961 is primarily remembered for Roger Maris and Mickey Mantle chasing Babe Ruth’s single-season home run record. But the Tigers won 101 games that season and led the AL race until late July when the Yankees finally overtook them and won by eight games.

Cleveland fans never got over the trade. Terry Pluto wrote a book called “The Curse of Rocky Colavito” sort of tongue-in-cheek blaming for the team’s long drought of World Series titles on a hex from the old slugger along the lines of the Red Sox’s supposed Curse of the Bambino.

Colavito never bore any ill will toward the franchise. He played again for the team for parts of three seasons in the mid-1960s, and in 1965 he led the AL in RBI with 108 and walks with 93 for Cleveland. After his playing days, he worked for the team as a TV announcer.

“To this day I don’t understand it nor do the Cleveland fans who still send me letters about it,” he told the Detroit Free Press on the 60th anniversary of the deal.

Any trade Jerry Dipoto makes

Frank Lane, the Cleveland GM who pulled off the Colavito trade, was nicknamed Trader for a reason, He would consider trading anyone. When Lane was the Cardinals, Peter Golenbock wrote in “The Spirit of St. Louis: A History of the St. Louis Cardinals and Browns,” Lane considered trading Stan Musial.

Mariners executive Jerry Dipoto is the modern equivalent.

The Seattle Times reported in March that since 2015, Dipoto had made more than 120 trades with the Mariners. The paper did not count minor transactions such as naming to named later.

When there’s that much activity becomes sort of a blur.

One commentator writer wrote this spring that after all the deals before this season, “I can’t tell if the Mariners are going to be any good.”

BONUS FRAMES

Getting fired for building a powerhouse

The day after Bing Devine got the boot as GM of the Cardinals, St. Louis’ greatest sports writer, Bob Broeg, wrote the team off for the 1964 NL pennant. Somewhat facetiously.

“Sorry, guys, to count you out so early this, but for the purpose of illustration, it must be done,” he wrote in Aug. 18 editions of the Post-Dispatch. After all, wouldn’t it look silly if you won the pennant after the general manager was fired because the big boss was “disappointed and frustrated”?

Broeg believed that August Busch, owner of the Anheuser-Busch brewery, was not so much impatient as he was in the thrall of Branch Rickey, his 82 -year-old special advisor.

Rickey is one of the most important figures in baseball history. He signed Jackie Robinson to integrate the game, created the farm system for player development and transformed the Cardinals from the No.2 team in a town too small for two MLB teams into a scrappy powerhouse.

Beer baron

Busch was not a big baseball fan. He bought the team in 1953 out of civic duty to keep the Cardinals from moving. Bill Veeck owner of the rival Browns was using his knack for showmanship in an effort to start outdrawing the Cardinals.

When Busch, with his deep pockets, bought the Cardinals, it spelled the end for Veeck’s hopes of taking the town. The Browns moved to Baltimore and became the Orioles.

After all more than a decade under Busch ownership, the Cardinals had won no pennants. They had finished second twice, including five games behind the Dodgers in 1963.

Rickey had come back to the Cardinals after 20 years away. Broeg likened him to Cardinal Richelieu, a power behind the throne who orchestrated the ouster of Devine.

The Cardinals entered play on Aug. 18th, 1964 in fight pace, nine games behind the Phillies. It looked bleak.

They still trailed by 6 1/2 games with 12 games left, but the Phillies collapsed. The Cardinals won the pennant by a game and beat the Yankees in seven games in the World Series.

From first to worst

The Sporting News still named Devine its Executive of the Year. And he landed on his feet. He succeeded George Weiss as general manager of the New York Mets, clearly the worst team in baseball, for 1965.

Devine spent three seasons building the Mets. His family stayed behind in St. Louis.

The Cardinals won the World Series again in 1967. In December of 1967, Devine was rehired as Cardinals GM.

The Cardinals won the National League pennant in 1968 but lost to the Tigers in seven games in the World Series.

The next season, the Mets won the World Series.

So Devine helped build two teams that won three World Series, and he was unable to celebrate any of them as part of the organization.